John’s Story

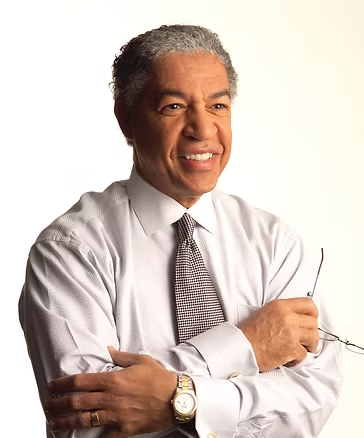

John T. Fleming

1997 Direct Selling Education Foundation Circle of Honor

2016 Direct Selling News Lifetime Achievement

2016 Direct Selling Association Hall of Fame

by J.M. Emmert

A comment from John: “This story is not being shared because it is my story. I share because it is a story about growing up, about the importance of family pride, community pride and most importantly - principles and values learned along the way... from family and others, many others who ultimately impacted my life and set me on a course that would not have been possible without their modeling and their intervention. Because we directly and indirectly impact the world by virtue of our stories, your story is even more important. I hope you enjoy reading my story.”

It should not surprise anyone who knows John Fleming that he initially balked at the thought of an article about him. The Direct Selling News ambassador and former Avon executive does not like the spotlight shining on him. He would much rather speak to the accomplishments of his family, friends and colleagues.

However, there is a fascinating backstory to this soft-spoken leader—much more than the 44 years spent advocating the direct selling business model or the more than 1,000 people he has personally brought into the industry. It’s a narrative full of heroes and role models who have shaped his life and fueled his ongoing commitment to serving others.

The Harlem of the South

Richmond, Virginia, was only a few decades removed as the capital of the Confederacy when Peter Ramsey established his dentistry practice there. The first licensed African-American dentist in the state of Virginia was John Fleming’s maternal great-grandfather. While Fleming has no memories of him, he can vividly recall life with Peter’s son, Mercer Ramsey, who followed in his father’s footsteps with his own dental office.

During the 1950s, Fleming and his parents, John and Essye, lived with Mercer on Leigh Street, an affluent section of Richmond lined with homes of successful African-American entrepreneurs of the day. Mercer was a well-respected businessman in Richmond and the earliest influence on Fleming’s life. “I looked up to him as a statesman, as a big deal,” he said. “It was the way he carried himself. He dressed up every day in a coat and tie, and was a very formal man in many ways. Most of all, he was a man of purpose.”

Fleming had come to live with Mercer after spending his first few years at Hampton Institute, known today as Hampton University, one of 105 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the United States. Fleming’s father had graduated from Hampton and then taken a job there teaching diesel mechanics during World War II. “He had an uncle that taught electrical engineering—and who is buried on the Hampton campus,” said Fleming. “My dad’s work was considered very important to the war effort, and he taught there for quite a few years before going back to Richmond.”

When he left Hampton and returned to Richmond, John Sr. went into business with his father running a full-service automobile center. “It was a combination of a filling station, auto repair center and convenience store that employed eight people,” said Fleming. While John Sr. was a college graduate, his father insisted that he work as a mechanic for the first few years to learn the business before eventually taking it over. That mandate from his father allowed John Sr. to cultivate business relationships with the African-American community as well as white businessmen in the city. He eventually became the first African-American to sell cars with a major dealership in Richmond.

“Dad had become friendly with the people who owned the Lincoln-Mercury dealership,” said Fleming. “He never worked at the dealership because at that time African-Americans were not allowed on the showroom floor. But because of his auto service business, he knew when people needed cars. So he would take them to the dealership, earning commissions on the sale of cars all while running the filling station.”

To Fleming, his father was a vocal, confident leader, completely different from his quiet, formal grandfather Mercer. “Dad was not quiet at all,” he said. “The biggest lesson I learned from him was confidence. He could talk about anything—whether national news, local politics or town gossip he seemed to be a voice in everything. I saw those leadership qualities in him.”

Those qualities were particularly evident in John Sr.’s interactions with Richmond’s leading black entrepreneurs. The family’s automotive center was located in a section of the city called Jackson Ward, where almost all of the businesses were owned by African-Americans. “Dad knew them all and they all patronized each other—whether it was hotels, nightclubs, restaurants or tailors,” said Fleming. “Second Street and Broad Street was a strip of black entrepreneurship no different than places in Harlem.”

In fact, Jackson Ward came to be called the Harlem of the South for the entertainment venues that brought in such musical legends as Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole. However, even a thriving business and entertainment community could not deflect what lay outside the boundaries of Jackson Ward—racial tensions that permeated Fleming’s day-to-day living.

A Mother’s Lesson

Fleming’s mother, Essye, called Garnet by her friends and family, had graduated from Virginia Union University, which like Hampton Institute was a historically black college. Her father, Mercer, had sent her to elite schools for African-Americans in Richmond, and she had chosen to pursue a career as a schoolteacher.

Garnet was protective of her only child. Richmond of the 1950s was a racially divided city, with no diversity in its neighborhoods. While her family members, the Ramsey’s, were prominent citizens in the African-American community, she knew that her son would encounter bias from the white population. Yet she never instilled hatred or fear in him. “She would never talk about it,” said Fleming. “Even when we went to Thalhimer’s, she would just go about her business.”

Thalhimer’s was a popular department store that enforced strict segregation laws. African-Americans were not allowed to shop with whites. “Mom went there to cash her check and we had to go to the third floor,” said Fleming. If we needed to buy anything in those early days, we had to shop in the basement.”

Even though Fleming has seen the “colored only” and “white only” signs on public bathrooms, water fountains, restaurants and other establishments, his mother never discussed the racial inequality but instead taught him which roads to navigate throughout the city. “My friends and I learned which neighborhoods we could ride our bikes into and which to never enter.”

Through those formative years, Garnet taught her son not only to survive but to thrive while growing up in such an environment. “My parents and the African-American community were always focused on education,” Fleming said. “Education was the answer to everything. As long as we were learning, our parents and grandparents knew that we were going to survive and be able to live healthy, successful lives as contributors to society. They might not have had a vision of what that might be, but they certainly did not have any limitation in their thinking.”

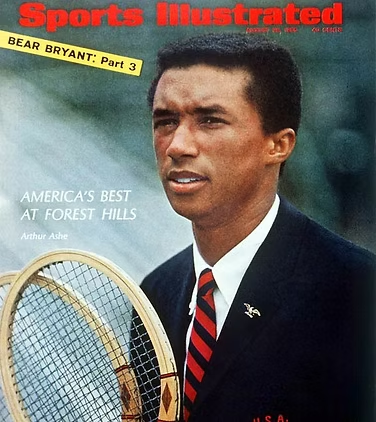

One area of Richmond that was very special to Fleming was the city playground. It was there that Fleming and his friends, including his good friend Arthur, would spend countless hours at the football and baseball fields, tennis courts, model aircraft field and public pool. Arthur, who lived in the groundskeeper’s house on the playground with his parents and brother, right next to the tennis courts, gave Fleming the first tennis racket he ever owned, a Bancroft wooden racket.

The memory of that racket would come to mind 18 years later as Fleming was driving from Chicago to Kankakee, Illinois. It was July 5, 1975, and Fleming was headed to a business meeting when he pulled his car to the side of the road to listen to a radio broadcast. On the other side of the world his good friend Arthur was about to make history. Fleming sat there listening as Arthur Ashe became the first African-American tennis player to win a Wimbledon Championship. “I know exactly what I was doing because it was such a big moment,” he said. “When I realized Arthur could win, I just pulled over and turned the radio up as loud as it could go.”

Fleming and Ashe had attended the same grade school, junior high school and high school. “There were not a lot of options for schools,” said Fleming. “In the area I lived there weren’t any schools, so many of us had to travel to another part of town. Lots of African-Americans who grew up in Richmond got to know each other so well because they were restricted in terms of the schools they could go to.”

However, his friendship with Ashe was not restricted to just school and the playground. Ashe’s father and Fleming’s grandfather frequently hunted and fished together, so Fleming had the opportunity to spend a lot of time with the rising tennis star. “Arthur was quiet but very confident,” said Fleming. “He was very smart, a great student. As for sports, you wouldn’t look at him and think ‘athlete,’ but he played baseball and tennis—and he was playing a lot of tennis before my friends and I realized he was getting very serious about it.”

During their junior year of high school, Ashe moved to St. Louis to work under a noted tennis coach. The friends reconnected years later and would see each other from time to time when both lived in New York in the 1980s. At a banquet in 1993, they spent some quiet time sharing the paths their lives had taken. Ashe, who had contracted the AIDS virus from a blood transfusion he had received during heart surgery, was finishing the manuscript for his memoir, Days of Grace.

Fleming told his friend of his involvement with direct selling, and Ashe, impressed with Fleming’s success, sent a follow-up note that opened with: “I should probably address you as Mr. Fleming now.” That sense of humor is one of the many things Fleming misses about his friend, who died two weeks later from AIDS-related pneumonia.

When Less Is More

At the time Ashe was pursuing his dreams of playing professional tennis, Fleming was focusing on his future. After graduating high school he had been encouraged to attend an HBCU as his parents had done. However, even though he was awarded a full scholarship to Hampton, he chose to enroll at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), a private university in Chicago noted for its engineering, to pursue his dream of becoming an architect.

His passion for architecture had been fueled by his paternal grandfather, also named John, who had opened the filling station (gas station). In addition to running the auto center, John and his brother, Byron, built houses, and Fleming had the opportunity to watch the building process on many occasions. “They knew everything about building homes, restoring homes and building cabinets,” said Fleming. “Uncle Byron lived in New York and came to Richmond from time to time to work on projects. If work was being done on a weekend, my grandfather would take me with him to the site.”

What intrigued Fleming most about the construction of the homes was the lack of really good blueprints. “These cats did not have a whole lot of plans,” he said, laughing. “They would talk about the building and what it was going to be like. And they would be building that thing as they talked. I would see them get stumped at certain times and go grab a stick and draw a plan in the ground as to how to make it work. But, in the end you would have a house.”

Although Fleming considered his grandfather a visionary—building homes without having a formal education or engineering background—he wanted the architectural training so he could pursue a career in the field. He spent the next five years at IIT learning the necessary skills and then landed a job with one of the most prestigious architects of the 20th century: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Originally from Prussia, Mies is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of modern architecture along with Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius. His major works, which included a mix of steel and glass, include the Seagram Building in New York and 860–880 Lake Shore Drive in Chicago. But while his architectural achievements are well-known, and his “less is more” and “God is in the details” aphorisms famous, it was the personal side of the man that Fleming came to admire.

On many occasions late nights at the office were halted by Mies in favor of a pizza party at his apartment, which was located just a few blocks away. Fleming and his associates would rush over there and stay up until dawn listening to Mies explain his language of architecture—his “skin and bones” approach—as well as his philosophy of life. It was during one of the late-night sessions that Fleming heard Mies address a comment that he was an interesting man. Mies’ reply was, “I don’t want to be interesting. I want to be good.” It was a phrase that stayed with Fleming for the rest of his life.

An Introduction to Direct Selling

Fleming knew that Chicago was the place to be for architecture, so it made sense to him to stay there and not return to Richmond. In addition, he had met and married a nursing school student named Joyce and had begun a family life that would result in daughter Kassandra and son John. However, the financial weight of a new family began to take its toll on him as he was earning only $19,000 a year as an architect. "Fortunately, Willie Larkin introduced me to direct selling," Fleming said.

“When Willie first approached me about it I thought it was the most hilarious thing in the world,” said Fleming. “I had a big ego about architecture. Architecture was my thing. It had been a dream for so long that it was hard to get away from it.”

But Larkin, a schoolteacher and a man Fleming greatly respected, was the type of person who had the ability to interact with people effectively, to bring out the best in people and to deal with real issues. He knew Fleming could use the opportunity to earn additional income. “He thought direct selling would be a way to build a business, be part of a distribution channel where you could develop customers all while receiving some pretty significant benefits,” said Fleming. “I always respected him because he was not a salesman or businessman but a schoolteacher with a lot of determination to do better. He helped me understand there are not many options in life to earn extra money. And every time I would complain to him about my financial stress, he would flip it around and ask what I was going to do about it.”

Larkin invited Fleming to be part of his Bestline Products direct selling business, which offered biodegradable cleaning products and, some years later, a skin care line and nutritional line. Fleming went to meetings with him and watched him demonstrate the products at home parties. “Joyce and I eventually held parties and became interested in the business opportunity,” said Fleming. “We did it in a very low-key, personal way—just a natural desire to share with others.”

It was during that time with Larkin that Fleming formulated his philosophy of direct selling. “Direct sellers do only three things: they sell and service customers; they share with others what others have shared with them; and they show others how to do what they are learning to do,” said Fleming. “If you understand it that way, then buzzwords such as ‘recruiting,’ ‘upline’ and ‘downline’ never interfere with your psyche because your definition is very simple and to the main point.”

After a year and a half of part-time involvement in direct selling, Fleming had earned $54,000. And so, in 1972, he decided to give up architecture and go full-time in direct selling. “The math said ‘you ought to spend more time on this,’” he said.

When Bestline became Better Living in 1976, the company owners wanted Fleming to take a corporate position as Vice President of Sales, which he did for several years. With his philosophy of the industry firmly grounded, Fleming set out to teach and advocate the principles and values of direct selling to others. “Direct selling has always been victim to people who over-promote extraordinary earning potential and under-promote ordinary earning opportunity,” said Fleming. “A few hundred dollars a month can change someone’s life if they manage it properly over time. That is one thing that is missing in the education of people who embrace direct selling. If we help people understand the basics of selling and the management of money, along with a positive attitude, goal setting, planning and personal development, then you have a business model that is unbeatable.”

That belief has in part been formed by the close friendships with direct selling legends that have so influenced him over the years—to the extent that he believes in what the business stands for when done right. “What attracted me to direct selling were people like Mary Kay, Mary Crowley (Home Interiors), Rich DeVos (Amway), Mark Hughes (Herbalife) and others who I would consider legacy founders and pioneers for the industry,” Fleming said. “They were simple and sincere in their explanation of direct selling. They said if you do a few things well, we will provide you with quality products and quality service, and that to me is the essence of a great company."

The Wild, Wild West

After 10 years with Better Living and a brief stint as CEO and President of the company and a merger with another direct selling company, Fleming decided to be a consultant for direct selling companies. He expected his first consulting job to last 12–18 months. Instead, it lasted 15 years.

Current Tupperware CEO Rick Goings was President of Avon North America when Fleming started his consulting business. Goings and then-CEO of Avon Jim Preston wanted to contemporize Avon—to “make the grand old lady run again”—and asked Fleming and former Shaklee executive Rich Perry to redesign the company’s compensation plan, create a new approach to training and implement what was to be called the Avon Leadership Program. “At the time, they had a single-level compensation plan,” said Fleming. “They did not reward on organizational structures except for a one-time reward for sharing the opportunity. There was no incentive for developing other people.” Fleming and Perry developed a new program in which Avon ladies could not only sell Avon products but also share Avon with others and receive benefits through three levels of compensation. As the project was coming to a close, Goings and Preston invited Fleming to be the project leader who would bring the new program to life within Avon.

“For me, it was like here’s the opportunity to play in the Super Bowl,” said Fleming. “I thought if I could learn to navigate these waters I would be able to do anything.” And so Fleming accepted and joined Avon as a director. Within four months he was promoted to Vice President of Sales Contemporization. Avon gave him an assistant who knew the ropes of the company, one who could both mentor him and help him meet the right people within Avon. “They put a lot of care into my development because they knew I could very easily fail based on inadequate relationships,” Fleming said.

Goings and Preston saw Fleming as someone who could come into the company and not upset the applecart while still contemporizing Avon. Upon his new appointment, Preston actually gave him just one mandate: Do this without disruption of the core Avon business. And while Goings and Preston had confidence in Fleming’s ability, they still gave him the low-performing Valley of California as his testing ground for the new program. “Avon had a good business along that western corridor, but the valley was isolated from San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles,” Fleming said. “The thought was if I screwed it up and could not make it work, it would not have a lot of impact on a lot of people. So it was the perfect area to do the pilot.”

Avon Division Manager Bill Singleton was part of the team that had designed the Leadership Program and then accompanied Fleming to California. While he would prove to be a critical member of the team, Fleming knew he needed one other person if the program was to truly succeed. That person was Vondell McKenzie.

McKenzie had worked with Fleming at Bestline and had been a manager at Tupperware. She had retired and was at the time touring the country in a motorhome with her husband. “I convinced her to come out of retirement because it was a unique opportunity before us,” said Fleming. “I knew her temperament would be good with the Avon reps as she was a strong, gentle woman. I went after personal talent because I knew I had to lead by example.” McKenzie would eventually become the first top leader in the newly contemporized Avon. Today, at age 78, McKenzie still earns hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, and Fleming still talks to her every few weeks.

“She is an example of people who transformed their lives as a result of the program,” said Fleming. “I think the good work we did in the field with the reps, in getting them to believe in a vision, to have faith and a willingness to learn got everyone to a better place.”

That might be considered a bit of an understatement. When Fleming took over the Western region it was the lowest-performing region in the Avon U.S. portfolio. There was no growth and Avon had been losing money there for quite a few years. In fact, the area was one of the major reasons why Goings and Preston wanted to contemporize the company. Within 18 months, however, Fleming and his team had turned it from the worst-performing unit to the top growth unit. And, for six consecutive years it was Avon’s best performing unit.

“We called our area the Wild, Wild West,” said Fleming. “We were so proud of our accomplishments. We used the theme song from Will Smith’s movie of the same name, and we celebrated at every meeting and every event.”

After more than a decade out West, Fleming returned to New York to work with current AdvoCare CEO Brian Connolly, then another Avon executive, to ensure that every region of the company received the benefits of the program. Fleming spent the next few years traveling the world, including stops in South America, Europe and Asia, to share the program with Avon reps.

Never Too Old

By Christmastime 2004, Fleming was considering retiring from Avon. He had been happy there, but there were other goals he wanted to achieve in life. So he called upon some of his closest friends to share his business plan with them. After reviewing the lengthy document, they looked at him and said, “John, evidently you do not realize how old you are.”

Fleming, then in his 60s, laughed along with the rest of the group. However, the comment evidently had little impact on him. On January 1, 2005, he gave his one-year notice to Avon and the following year accepted the publishing duties of Direct Selling News. Though the position was not in his business plan, he considered it a great opportunity for him to continue his advocacy of the industry. “I felt I still had things to say about the business model that could be beneficial for the hundreds of thousands of people coming into the industry hoping it was the answer to their prayers,” he said. Over the next eight years he would build a trade publication that is today the most respected journalistic resource ever created in support of the direct selling industry. In reflection, John said: Had it not been for Stuart Johnson, friend and owner of Direct Selling News who provided the opportunity, the direct selling industry might be just a bit different today In some very important ways…. that’s the kind of impact Direct Selling News was able to have and it all started with Stuart and a great vision! I am delighted to have been a part of it!"

Fleming has always remained focused on those personal goals he had shared with his friends. He had never forgotten how his parents and grandparents had stressed the importance of education—and how it had made a difference in his life. He wanted to give back to the younger generation by inspiring students to stay in school and further their studies. Of particular importance to him were minority students, which had the highest and most alarming high school dropout rate in the country.

In 2006 he founded Black Educational Events (BEE) with his son to raise awareness of the importance and relevance of HBCUs, which both his parents and children had attended. Over the next three years, Fleming personally financed the Angel City Classic, an annual event that brought HBCUs to the West Coast. Held at the Los Angeles Coliseum, the Classic featured football games between Morehouse College and Alcorn State University (2006), North Carolina A&T and Prairie View A&M (2007), and Morehouse and Prairie View (2008). The two-day events also included a Battle of the Bands and educational forums for the more than 50,000 students and parents who attended each year. In 2009, Fleming continued his support of HBCUs by financing HBCU Today, a 300-page comprehensive guide on all 105 HBCUs that he is currently converting to digital format to distribute to schools and libraries.

In 2008, Fleming went back to his architectural roots to write The One Course, a guide for building successful lives. Using the principles learned from Mies and his training at IIT, Fleming offers readers the basics to becoming the architects of their own destinies. “Everything created is the result of specific principles and processes at work,” said Fleming. “Therefore, it is only natural and logical that we should approach the design of life the same way.”

In addition to becoming Executive Director of the SUCCESS Foundation in 2010, Fleming has continued to keep busy with his DSN duties as well as his special projects. However, his passion for direct selling is equaled by his desire to find the means to further support educational initiatives. He has traveled to Washington, D.C. on several occasions to meet with the leaders of the White House Initiative on HBCUs and has had meaningful dialogue with corporations and organizations interested in seeing minority students realize better futures.

It is the desire to serve others that keeps Fleming going strong in his 70s. “As longas we have our health, our belief system intact and some talent that allows us to do something, I keep this belief that we can overcome the most amazing adversity,” he said.

“I think that is because I have always been around so many people who achieved the extraordinary in their lives. Enough of it has always rubbed off on me. It begins to permeate and become a part of you. When you surround yourself with goodness and principles and values that are sustainable, you can withstand the quirks in life.”

A Lifetime of Achievement

John Fleming has been witness to some extraordinary firsts in his lifetime, from his family and friends to those he has met and worked beside in the direct selling industry. This past April, at the DSN Global 100 Celebration of the top direct selling companies in the world, Fleming achieved a first.

In acknowledgement of his 44 years in the industry and his ongoing commitment to advocating the business model, Fleming became the first recipient of the Direct Selling News Lifetime Achievement Award. It was the second time he has been recognized by his industry peers; in 1997 the Direct Selling Education Foundation inducted him into its Circle of Honor.

In true Fleming fashion, he accepted the DSN award as he has lived his life: humbly, gratefully and with appreciation for those who have helped him along the way. Direct selling has, in many ways, helped to form the principles and values by which he lives—to share his knowledge with others so they can create better lives for themselves and their families. It is the foundation on which he has been able to successfully serve others.

As another example of well-deserved praise, Fleming was honored again in June of 2016 with induction into the Direct Selling Association Hall of Fame, making him the only individual, at this time, to have received the triple crown in direct selling.

There is a quote that seems remarkably fitting for Fleming as you consider his life and his passion for helping others. It is this: “True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever costs, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.”

That quote is from Arthur Ashe and, surely, he is smiling from above as he watches his good friend John Fleming embody those very words.